Weekly Impressions

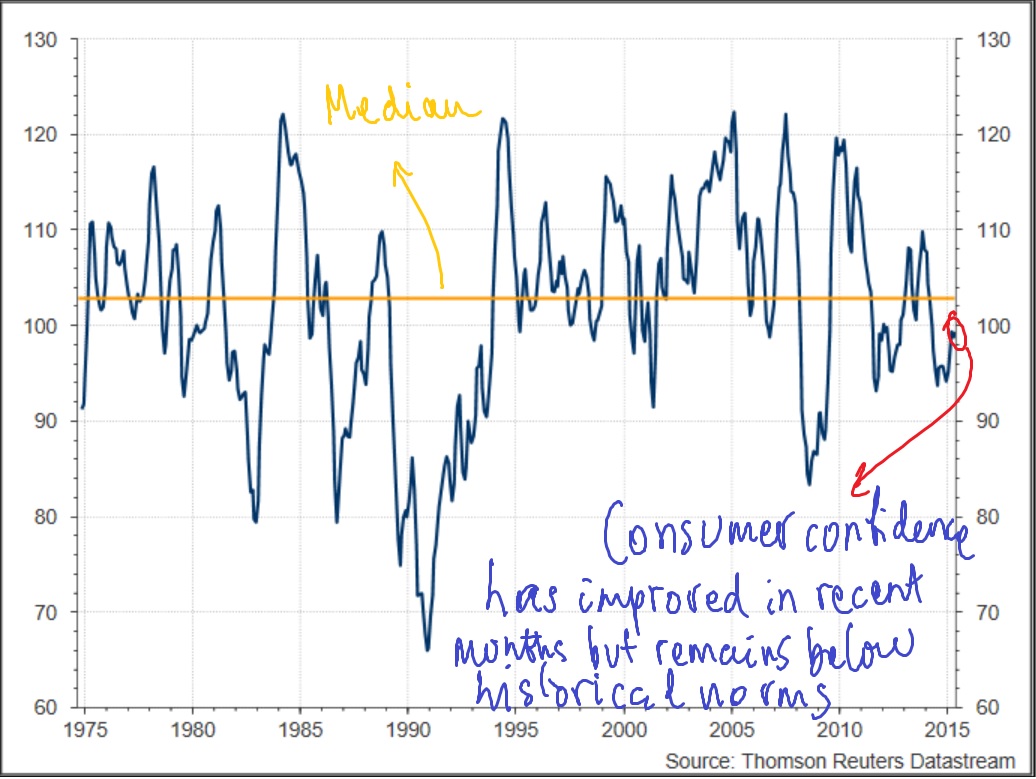

/In another turbulent week for global stock markets, the S&P500 moved sharply lower overnight, shedding over 3%, apparently on continued concerns about China's future growth prospects following the weaker than expected manufacturing survey mid-week and renewed volatility in the Shanghai Composite Index.

The key question for investors is whether US stocks at current levels, represent good value now. Despite the correction in recent months, the stock market still doesn't look particularly cheap, with the 12 month forward PE on the S&P500 of 15.7x still higher than historical norms (see chart). The headwinds facing US stock investors stem from the stagnation in expected profitability over the past 12 months. This follows a rapid recovery in profitability from 2009 to 2011, followed by more modest upgrades from 2011 to mid-2014. Since then, growth prospects have remained broadly unchanged, in part reflecting the appreciation of the US dollar. An effective tightening of monetary policy - thanks to the end of QE and imminent end to the Fed's policy of forward guidance - probably has been another headwind facing corporate America.

The ASX200 fell by around 5% during the week to its lowest level since December 2014. The start of the year now seems a very long time ago, when synchronised monetary easings by over 20 central banks - including the RBA - over the course of a month - helped to propel stocks higher. Analysts have marginally downgrade future growth prospects for the ASX200 companies in aggregate year to date, which means that the 12 month forward PE of 14.5x is little changed from the end of 2014 and in line with historical norms.

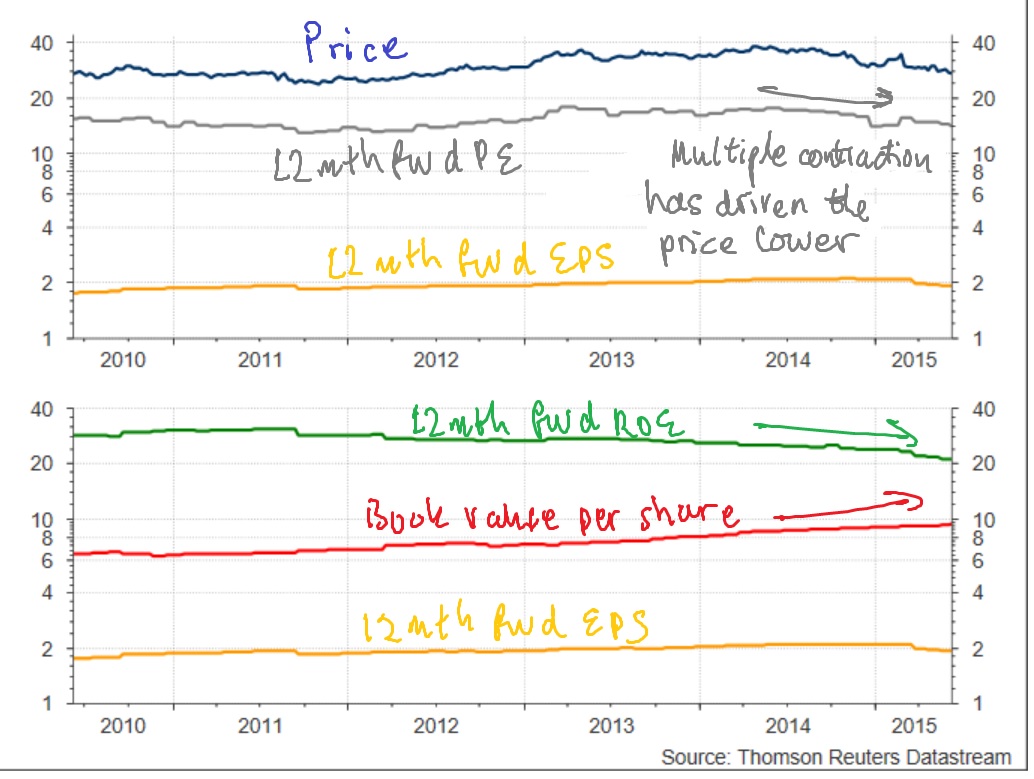

Future growth prospects of the ASX200 have now stagnated for almost five years, so episodes of multiple expansion and contraction have driven market volatility over this time. Since mid-2013, the 12 month forward PE has hovered in a narrow range of 13x to 16x, so the current PE is at the mid-point of the range, making the market look neither cheap or expensive at current levels (see chart).

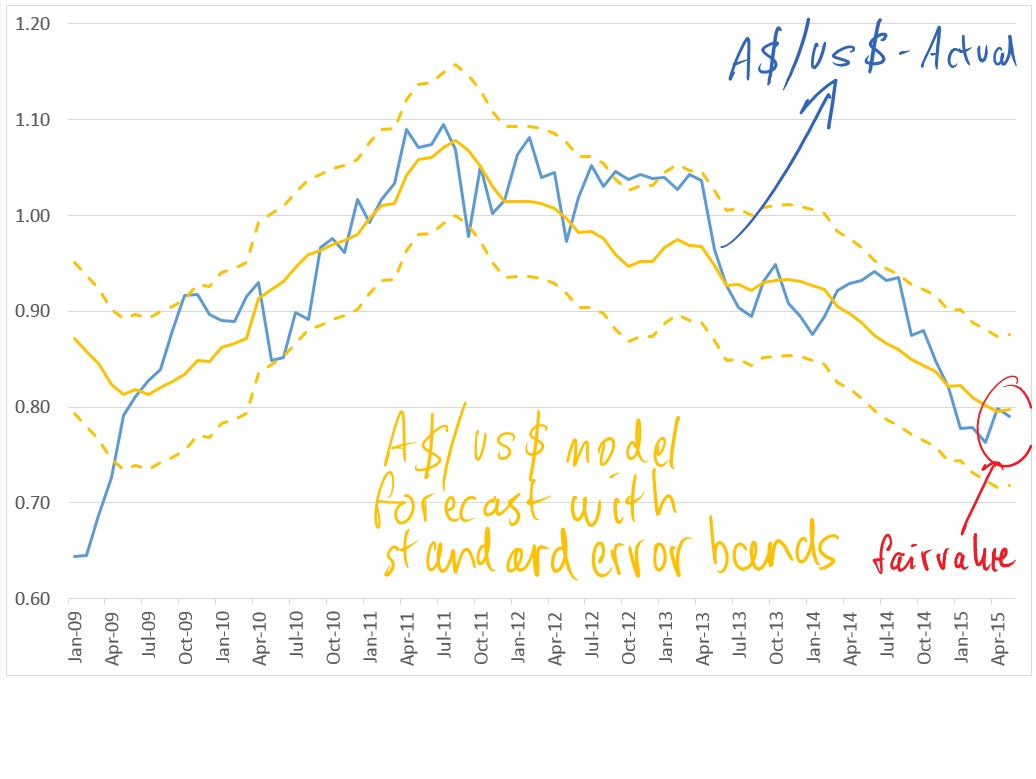

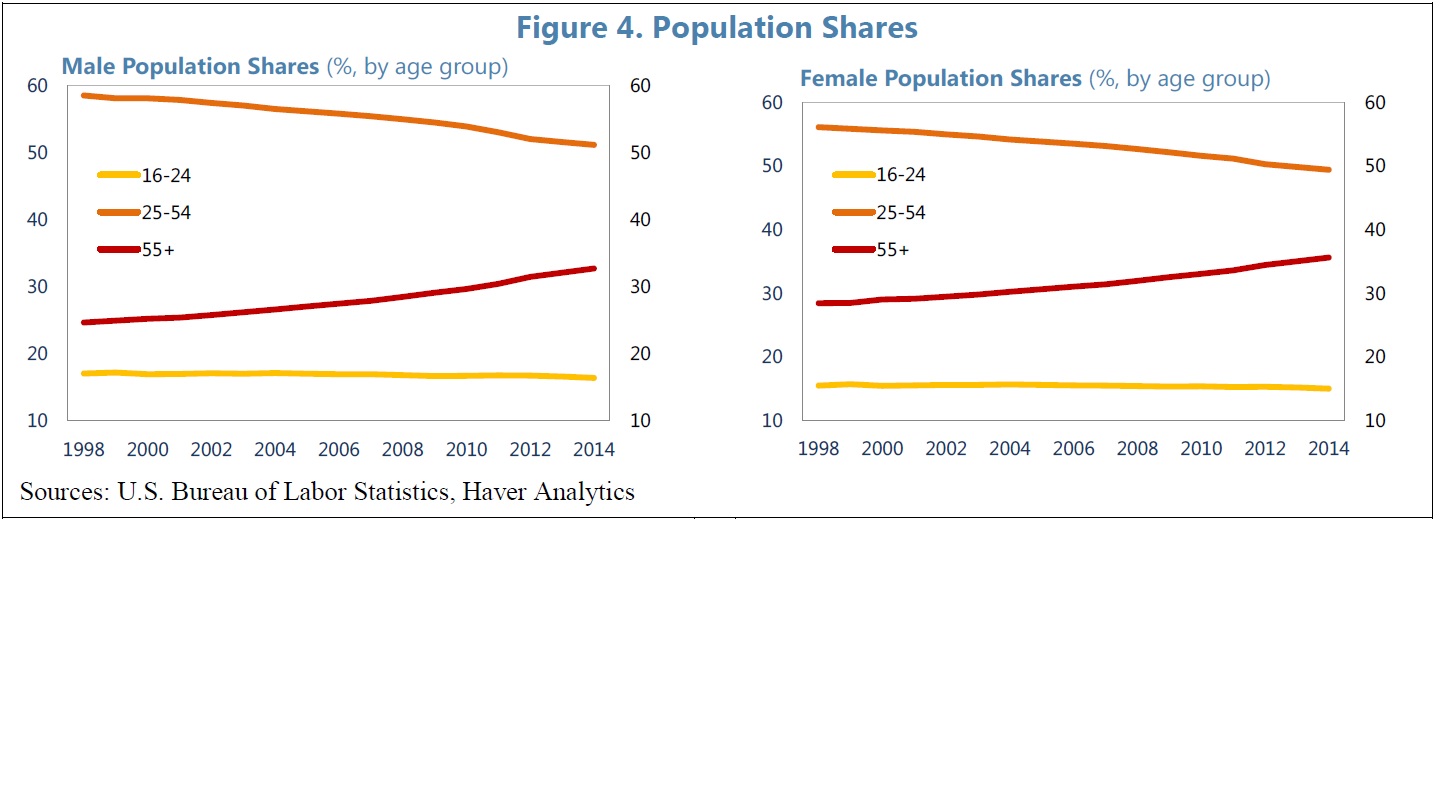

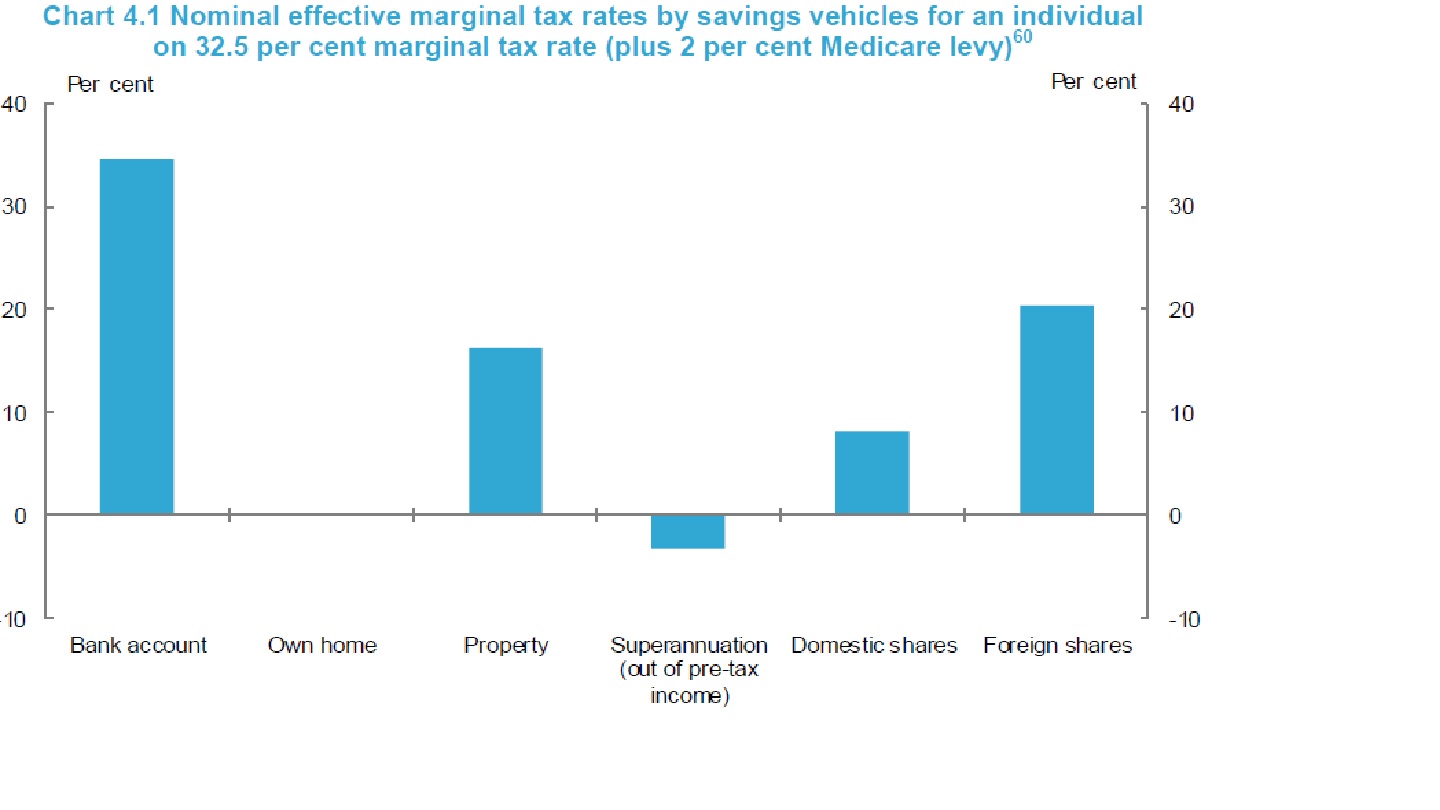

Beyond the cycles of multiple expansion and contraction, a pick-up in earnings growth is the necessary ingredient to drive the market sustainable higher. But while the Australian economy remains stuck in a nominal funk, revenue headwinds will remain persistent. Margin expansion can only drive profitability so far. Since global commodity prices peaked in mid-2011, growth in nominal GDP has been even more anaemic than the early recession of the early 1990s. In previous posts, I have suggested - contrary to conventional wisdom - that the RBA has been too slow to respond the negative terms of trade shock, which have declined by over 50% from the peak. The central bank has been more concerned about the composition of growth - hoping that net exports and non-mining capital spending would drive growth - than overall growth in nominal GDP.

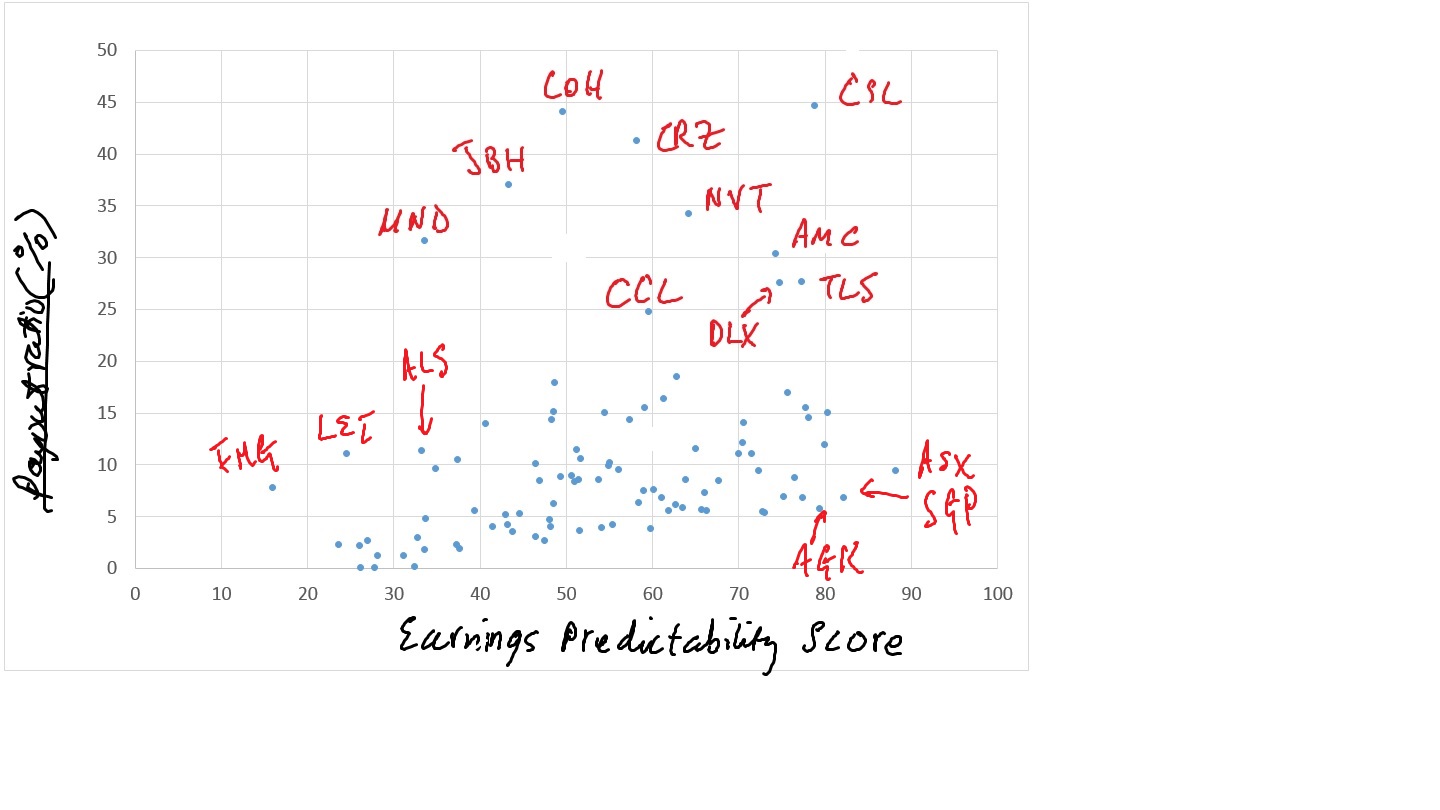

Evidente has also previously highlighted that the five year long stagnation in growth prospects for the ASX200 is testimony to the resilience of corporate Australia, considering the stiff revenue headwinds that companies have faced. Companies have trimmed costs aggressively, undertaken restructuring, sold off underperforming and non-core assets, and deferred capex where feasible. Some analysts have taken a glass half empty view of the weakness in business investment, interpreting this as evidence of under-investment in future growth. But most investors have rightly taken a glass half full perspective, and ascribed tremendous value to companies that have foregone investment opportunities that do not meet their cost of capital requirements, and returned capital to shareholders, predominantly in the form of higher dividends.

At a time when the terms of trade has shed 50% and future earnings growth prospects have stagnated, it is remarkable that analysts' dividend forecasts are one third higher than five years ago (see chart).

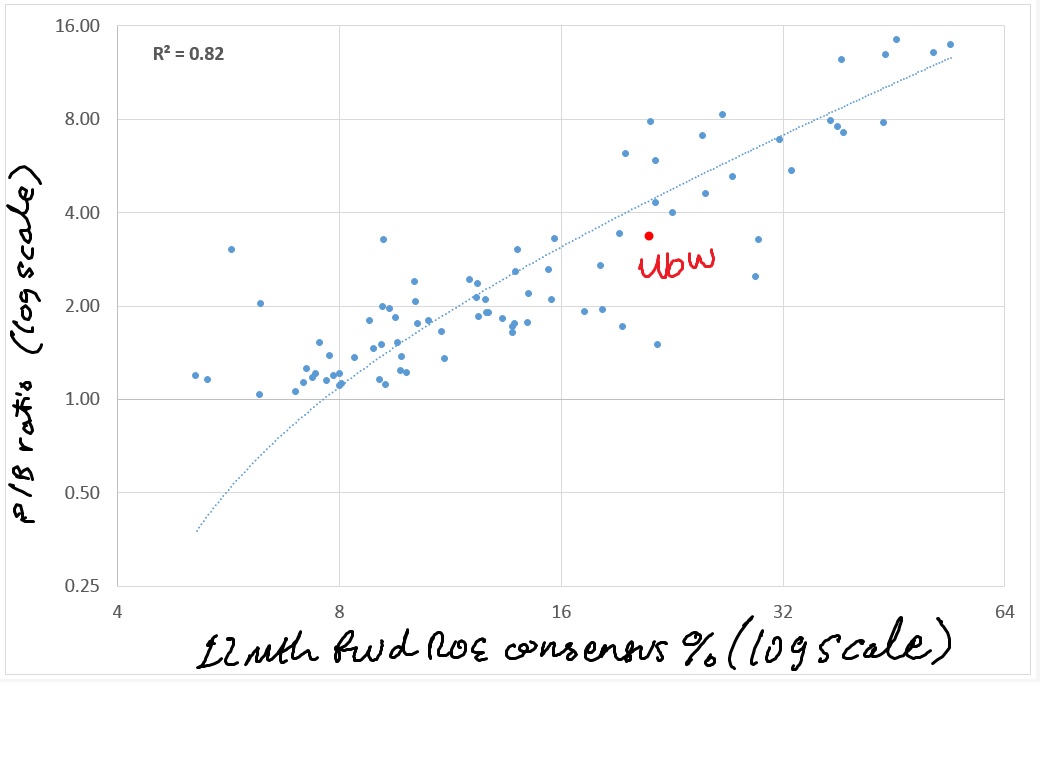

At the stock level, even small earnings misses continue to be punished by the market, notably Seek and Dick Smith Holdings. Given the stellar rise of Seek over the past decade as the dominant online platform for job ads, the 10% fall on the result garnered plenty of news flow, namely comments from the CEO that investors remain subject to short termism, and exhibit little patience for Seek's plans for global expansion. There might well be an element of truth, but Seek is not being singled out by investors. After all, the equity risk premium has increased in recent years, as investors have lost trust in CEOs to undertake value accretive investments and acquisitions. But the adverse reaction to SEK's results reflects the fact that analysts' growth expectations had become excessively optimistic. Not only did analysts' earnings upgrades for the stock start to slow in early 2015, but have started to downgrade the company's growth prospects in recent months (see chart).

Other high growth stocks that have been subject to growth stalls or downgrades in recent months include REA and Carsales (see chart). Domino's Pizza has bucked the trend, with analysts continuing to upgrade the company's future growth strongly in the past year.

For high growth stocks trading on rich multiples, even small earnings misses can lead investors to re-assess the company's longer term growth prospects. Consequently, investors have de-rated SEK, REA and CAR (see chart). Given the top-down headwinds that have buffeted corporate Australia cited above, the aggregate supply of growth has been scarce over the past five years. In hindsight, those few stocks that offered strong growth prospects were strongly bid up by investors. For Domino's, the risk it that its strong growth profile has become even more scarce in an environment where the growth prospects of other market darlings have stalled.