A loss of trust and the Quiet Revolution in Corporate Governance

/"Payouts to shareholders reduce the resources under manager's control, thereby reducing managers' power...Conflicts of interest between shareholders and managers are especially severe when the organisation generates substantial free cash flow. The problem is how to motivate managers to disgorge the cash rather than invest it at or below the cost of capital... "

- Professor Michael Jensen, 1986, Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance and takeovers, American Economic Review

Commentators and analysts continue to be vocal critics of the insatiable appetite for income that investors have developed in recent years. The argument goes that this trend has encouraged companies to return capital back to shareholders in the form of higher dividends and buy-backs, at the expense of investing for future growth. Thus, companies are apparently foregoing valuable growth opportunities stemming from investors' short-termism. Although record low interest rates has probably contributed to the 'reach for yield' in financial markets, this post argues that investors' loss of trust in CEOs' ability to undertake value accretive projects and acquisitions has had an important influence on corporate payout policies. Moreover, the greater propensity for companies to return capital back to shareholders has been far more powerful in reducing the agency costs of free cash flow than the noise created by the bloated ESG industry.

Since the turn of the century, the finance industry has becoming increasingly noisy in extolling the virtues of good corporate governance thanks to a number of high profile governance failures, including (but not limited to) Enron, Parmalat, Tyco, WorldCom, Lehman Bros and closer to home, HIH Insurance.

Australian asset managers have led their world in their march to being good corporate citizens; the take up of the United Nations Principles of Responsible Investing is among the highest in the world. The mainstreaming of environmental, governance and social factors (ESG) has meant that most active funds showcase their ability to incorporate ESG into their investment processes.

Many ASX listed companies have catered to the greater investor appetite for good governance by appointing more independent board directors, lifting the level of disclosure in annual reports, adopting remuneration structures that are designed to align the interests of senior management and shareholders, establishing audit and remuneration committees, and separating the roles of chairperson and CEO. CEOs are astute enough to give investors what they want, particularly if it involves a low cost, low effort box ticking exercise. Little surprise then that there has been a pattern of inflation in governance scores over the past decade, but it is far from clear that the greater awareness of governance issues has properly addressed the classic agency conflict that arises from the separation of ownership and management of corporate assets.

Despite the 'noisy' revolution in corporate governance (and ESG more generally), has the upheaval in governance practices led to improved company outcomes globally? In their pioneering study published in 2003, Paul Gompers et al demonstrated a strong empirical link between governance and performance in the United States through the 1990s; stocks with strong shareholder rights strongly outperformed and had higher firm value, higher profits, stronger sales growth, lower capital expenditures and undertook fewer corporate acquisitions. But a more recently published study in 2012 by Lucian Bebchuk et al shows that although well governed firms continued to exhibit superior operating performance from 2000-08, they did not outperform stocks with weak shareholder rights. The authors attribute their finding to investor learning; there was a greater awareness of, and attention paid to governance by investors, which meant that good governance was already impounded into stock prices.

Anecdotal evidence also casts doubt on the link between good governance and stock returns; firms with weak shareholder rights and few independent board directors continue to deliver strong stock returns, including Apple, Newscorp, Westfield and Harvey Norman to name a few.

In his pioneering study from almost three decades ago, Michael Jensen argued that the separation of ownership and management of corporate assets gives rise to more severe agency conflicts when a company generates strong free cash flow, because there is scope for the CEO and senior executives to use the free cash flow to expand the size of the firm at the expense of profitability and shareholder returns. Returning cash to shareholders therefore imposes a powerful discipline on the CEO, "...making it more likely they will incur the monitoring of the capital markets which occurs when the firm must obtain new capital."

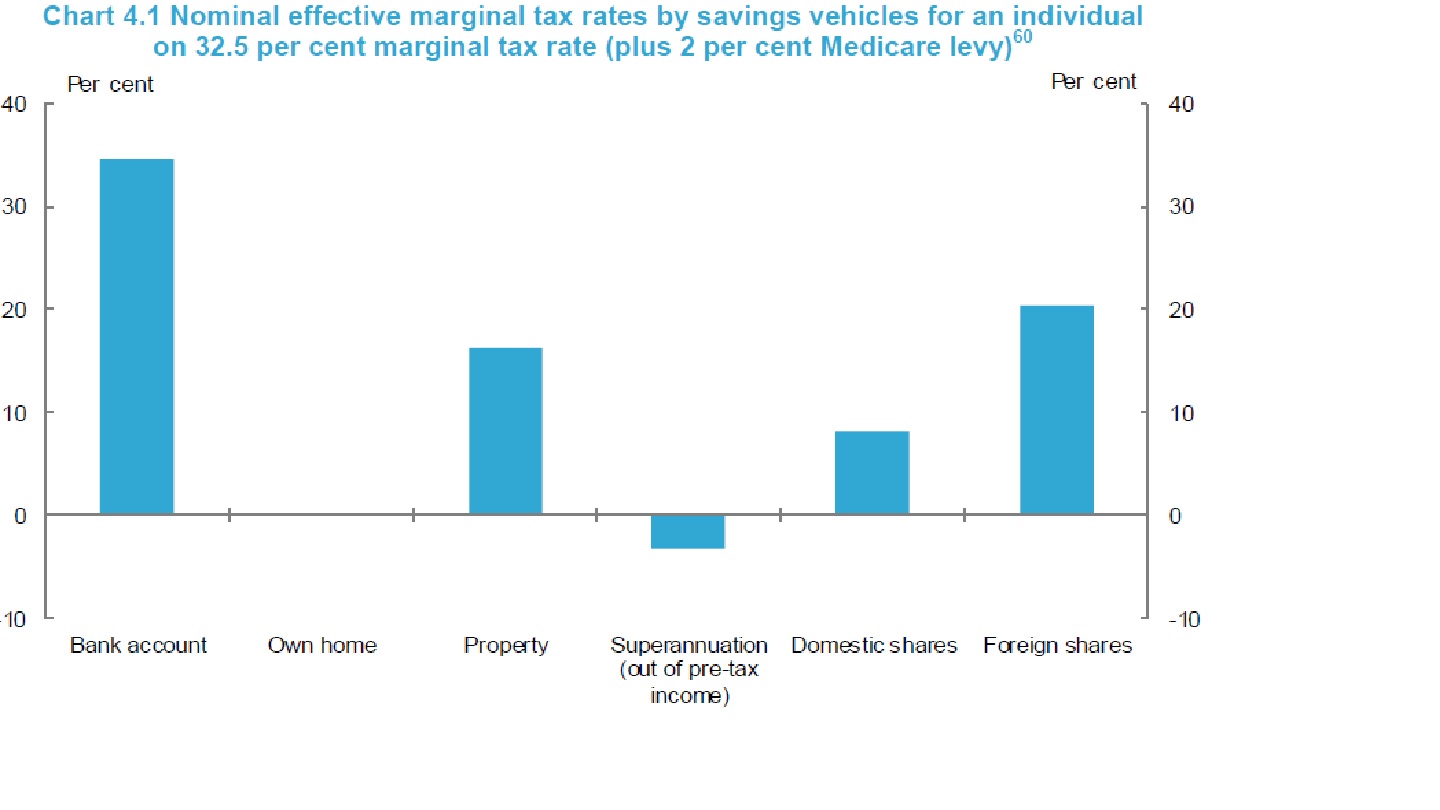

Australian firms have for a while now had a higher dividend payout ratio than their global peers thanks to the adoption of the imputation system in 1987, which eliminates the double taxation of corporate profits that are paid out as dividends since shareholders receive an imputation credit for the tax already paid on profits by the company. The aggregate payout ratio started to lift from the 1980s.

But more recently, companies have increasingly resorted to returning cash to shareholders in preference to re-investment and acquisitions. For starters, dividend concentration has risen; the top 10 dividend payers in Australia generate 60% of aggregate dividends paid by All Ordinaries companies, well above the 43% generated at the peak of the credit boom in 2007 (see chart).

Second, the aggregate payout ratio has lifted in recent years, to its current level of 70%, above the median of 65% since 1990 and well above historical trends over the past forty years (see chart). The payout ratio has exhibited a strong cyclical pattern since the early 1990s, with sharp rises associated with either a contraction or stagnation in earnings, while the aggregate dividend per share has exhibited far less variability, confirming that companies engage in dividend smoothing.

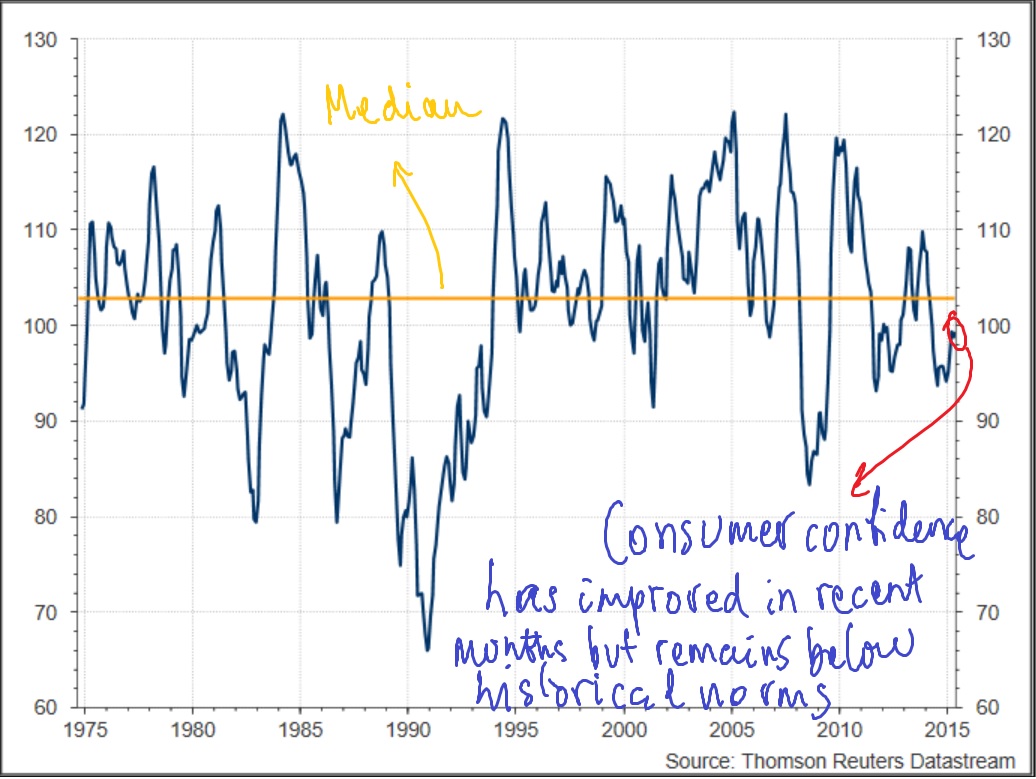

The sustained lift in the payout ratio represents the flip-side of the corporate sector's dormant animal spirits. The RBA Governor, Mr Glenn Stevens, has bemoaned the lack of risk taking in corporate Australia and implored businesses to invest for future growth. But more recently, Mr Stevens and the RBA have acknowledged that the hurdle rates used by companies to evaluate future projects has remained sticky despite the fact that 10 year government bond yields remain close to record lows.

The financial crisis continues to cast a long shadow

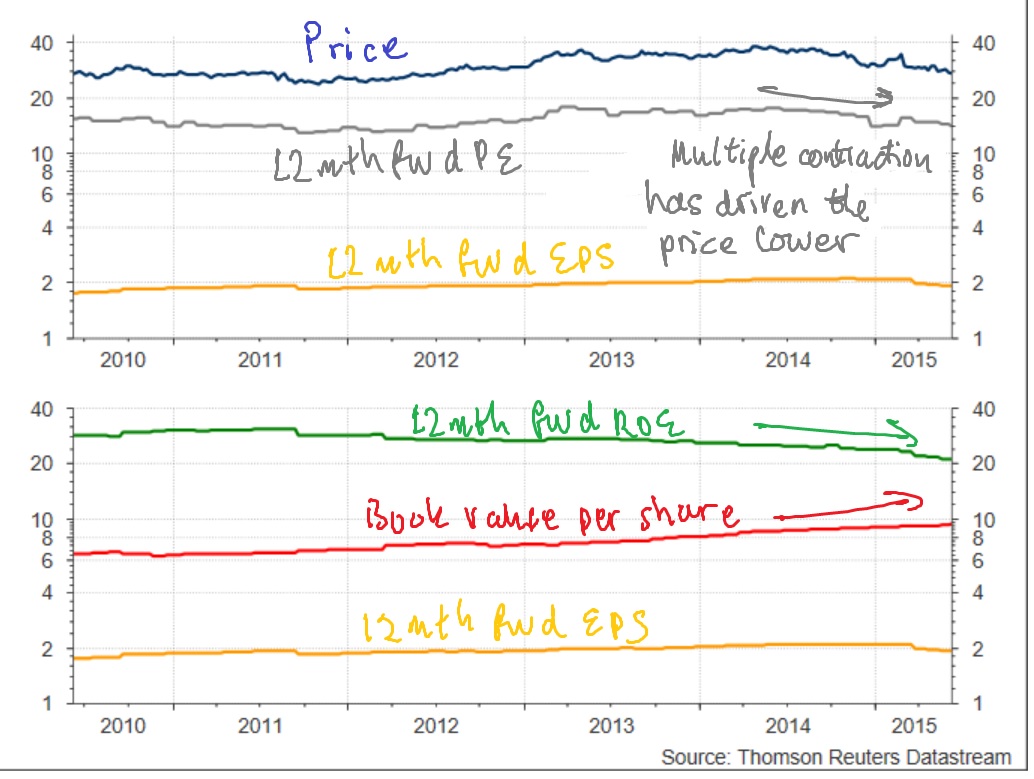

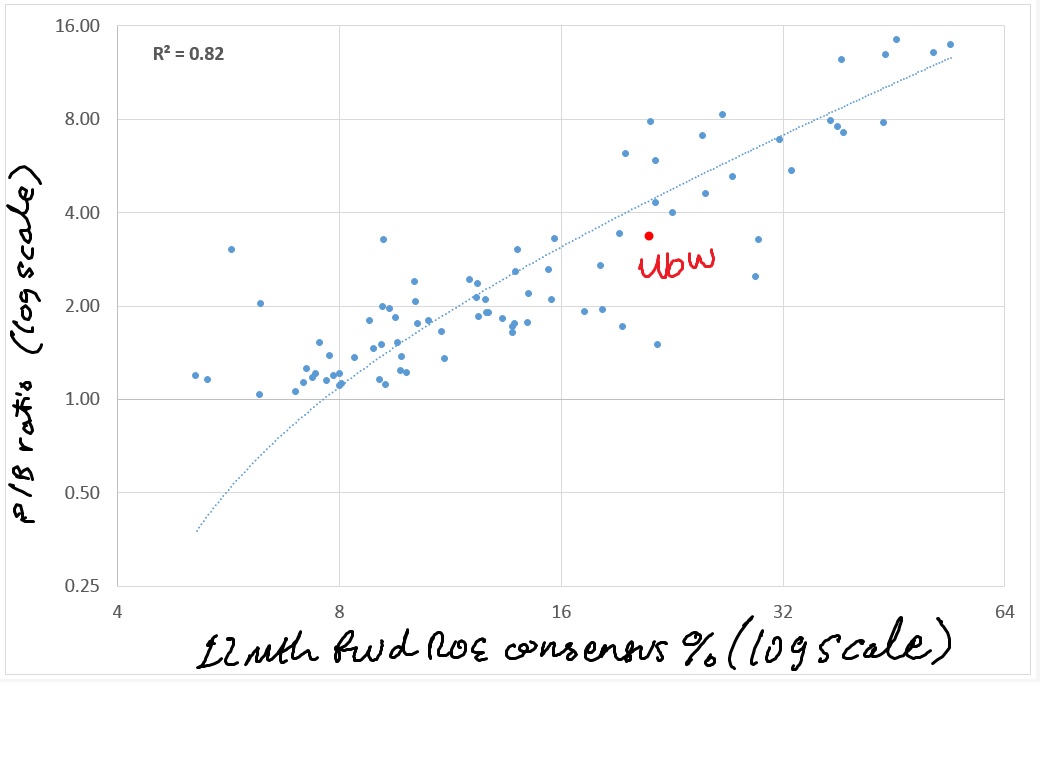

I believe that the insatiable appetite for income that investors have developed has arisen in large part to a loss of trust in CEOs' ability and willingness to undertake value accretive projects and acquisitions. The poor track record of acquisition led growth through the credit boom of the mid-2000s has left investors justifiably cynical of CEOs' motives: RIO, BHP and QBE are just some that come to mind that have undermined investors' confidence.

Marrying payout and predictability

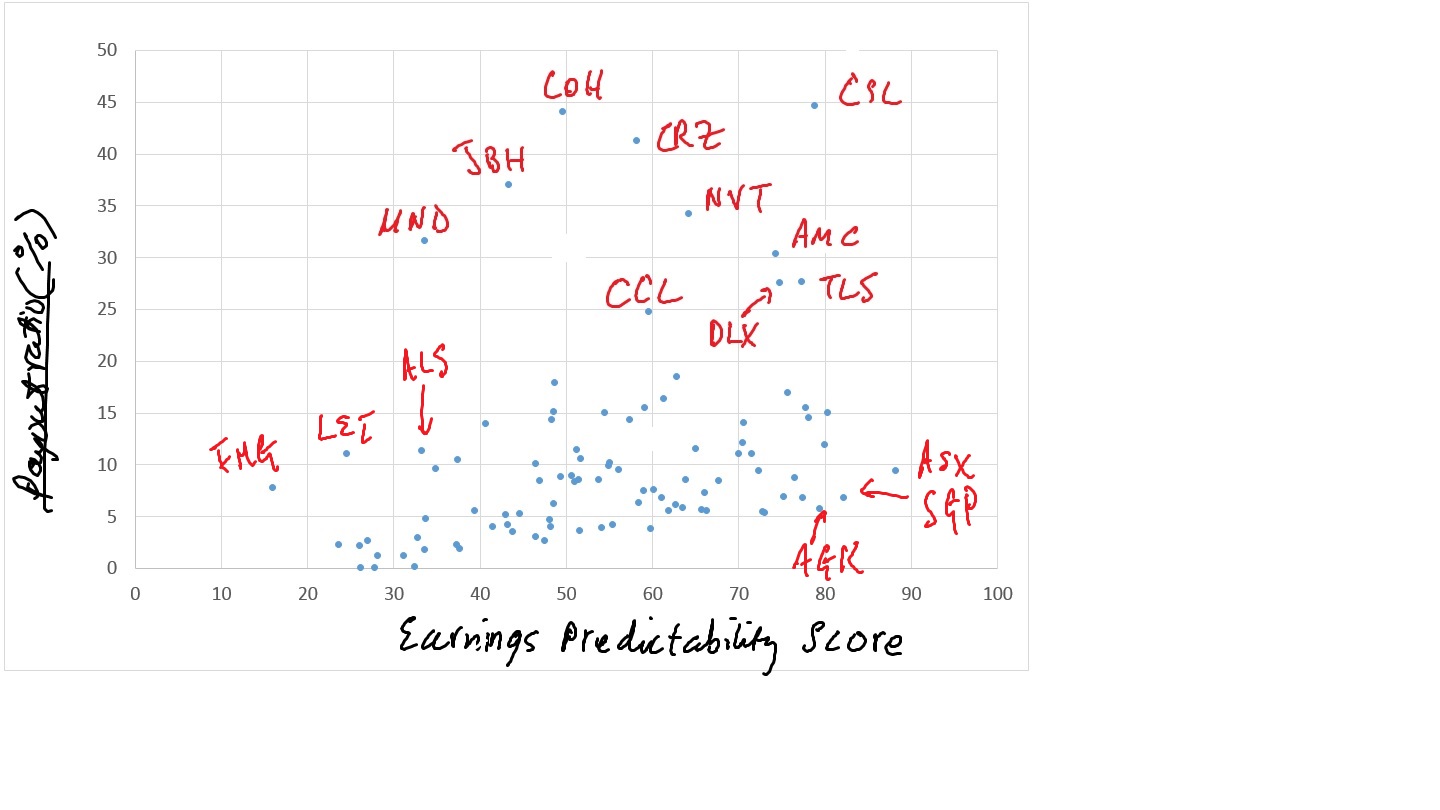

I have developed a score for a company's payout ratio based on past dividends paid and stock buy-backs undertaken (see chart below). I use total assets rather than EPS as the scaling variable due to the volatility and cyclicality of EPS for some companies. Stocks that rank strongly across this metric include CSL, COH and CAR.

Separately, I have developed a proprietary composite indicator for a stock's earnings predictability based on five variables. The chart below plots the earnings predictability score against the aggregate payout ratio. The plot identifies a number of stocks with potentially unsustainably high payout ratios because their predictability scores fall below the median, notably JBH and MND. Three stocks that appear to have scope to lift their payout ratios due to their strong earnings predictability include: ASX, SGP and AGK.

The other revolution in corporate governance

It is a welcome development that CEOs with a track record of acquisitive growth no longer command a premium in the market for managerial talent. Boards increasingly are looking for CEO candidates that have a track record of prudence and cost control, and that exhibit a willingness to abandon under-performing assets that in the past might have been seen to represent future growth options, but are increasingly now viewed as peripheral and distracting from the company's core focus. This 'other' revolution in corporate governance will be the subject of a forthcoming report from Evidente.