Beware of bubble talk, for now (Part II)

/In last week’s blog post, I discussed a wide ranging speech delivered by the RBA Governor in New York on April 21st (The world economy and Australia), in which he acknowledged that corporate Australia’s capital restraint of recent years reflected in part the fact that the cost of capital or hurdle rates used in capital budgeting decisions had remained sticky. Despite the reduction in rates of return available on safe assets in Australia and globally, there has been an offsetting rise in the expected equity risk premium. Sovereign bond yields globally have declined to record lows precisely because investors expect to be compensated more for taking on stock risk.

At times in the past year, having bemoaned the absence of entrepreneurial risk taking in Australia and implored businesses to invest for future growth, Mr Glenn Stevens’ comments provide the clearest indication yet that the RBA understands that animal spirits will be dormant for as long as the risk premium remains high. The central bank's conduct of monetary policy over the course of this extended easing cycle suggests that it continues to under-estimate the power of monetary policy to influence the psychology of risk taking. I concluded in last week's post that the risk premium would remain high and that multiples on low beta or defensive securities would remain elevated for as long as the capital discipline remains pervasive across corporate Australia.

A recurring question from portfolio managers that I spoke to last week related to the 'when' and 'what'; when will entrepreneurial risk appetite return and what range of indicators represent an accurate barometer of the risk premium? I believe that the labour market provides fertile ground because new cost discipline has extended to a reluctance by businesses to hire in recent years. Further, the labour force survey is a higher frequency and more up to date indicator than the capex survey compiled by the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

The market understands the significance of labour market conditions at least for monetary policy deliberations; the implied probability of a rate cut at the RBA's May board meeting declined to 55% from over 75% immediately following the release of stronger than expected March employment data in mid-April (see chart).

But investors might have been premature in discounting the chances of another rate cut because a range of indicators point to still considerable slack in the labour market. The persistent weakness in labour market conditions provides compelling evidence that the corporate sector's animal spirits remain dormant.

Record low wages growth

Growth in private sector wages has been moderated for over three years now, and the current annual rate of 2½% represents the slowest pace of growth on record, confirming that demand for labour remains subdued (see chart).

Strong discouraged worker effect, particularly among young people

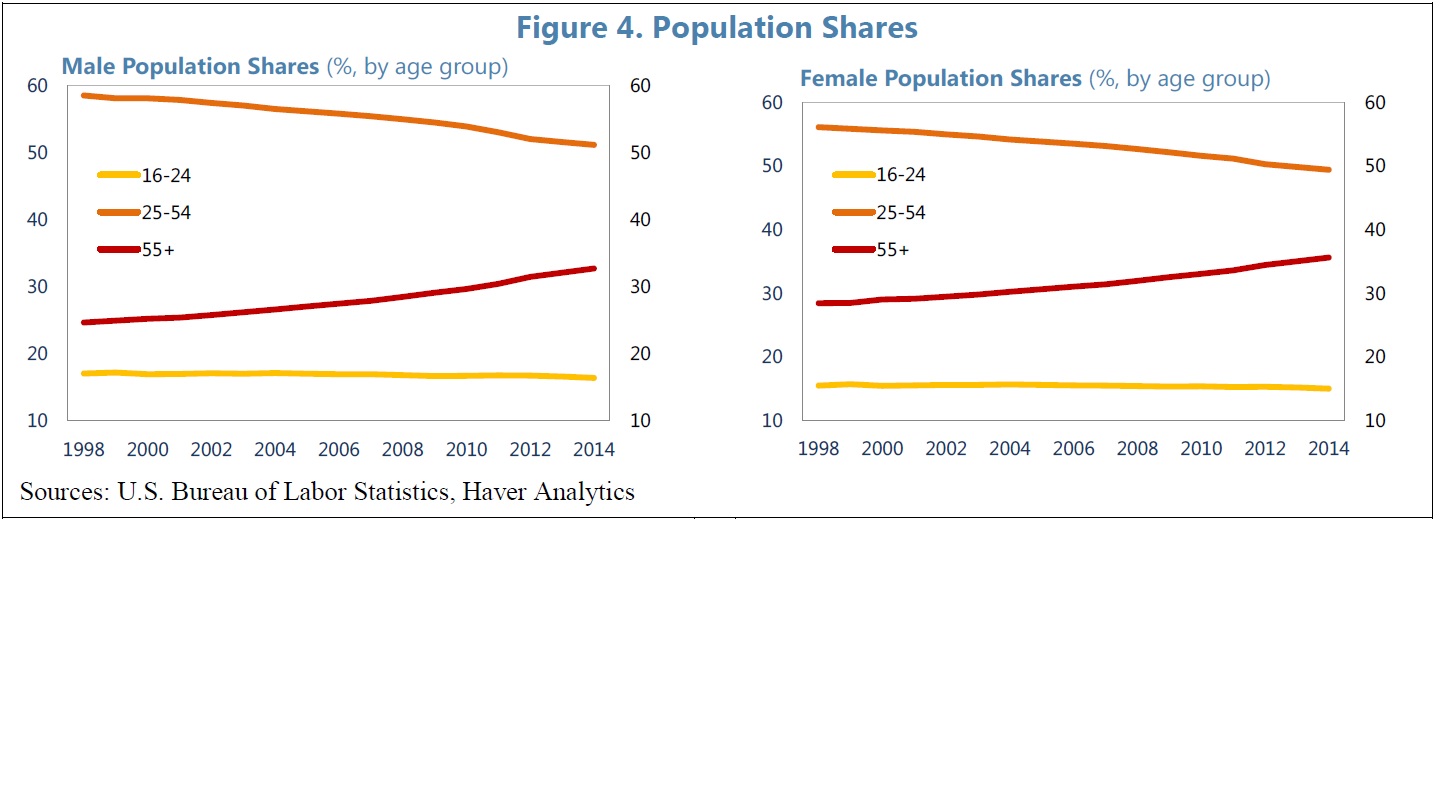

The participation rate has stabilised at between 64½% and 65% in the past two years, but this remains at its lowest level since 2006 (see chart). The low participation rate points to weak cyclical conditions which discourage people from seeking jobs, and also reflects the demographics of ageing because older people typically have low rates of labour force participation. The decade low level in the ratio of employment to working age population confirms that cyclical weakness in labour market conditions.

The discouraged worker effect seems to have been especially strong among young people (those between the ages of 15 and 24). The participation rate among young people declined to a record low of 66% in 2014, down from 71% in 2008 (see chart). Professor Jeff Borland, a labour market economist at the University of Melbourne, draws attention to the fact that the labour market for young people is particularly sensitive to cyclical conditions. The number of young people looking for work tends to drop sharply during a downturn because hiring rates typically decline and young people account for a disproportionately high share of new hires. Early signs of a revival in job prospects among young people have emerged in the past six months, although the participation rate of 67% remains low by historical standards.

Downward trend in average hours worked

Total hours worked has continued to grow, assisted by strong population growth, but average hours worked has been roughly stagnant now for two years and remains well below its level in 2006 (see chart).

Hiring intentions remain subdued

Forward looking measures of labour market conditions remain weak. Both the level of job ads and job vacancies are below 1.3% of the labour force, suggesting that businesses remain cautious in their hiring intentions (see chart).

Australia's unemployment rate is high by international standards

Australia's unemployment rate has remained above 6% for ten consecutive months, the longest stretch since 2003 (see chart). In fact, the unemployment rate in Australia of 6.1% remains well above that of the United Kingdom, Japan, United States and New Zealand (see chart).

Unemployment duration continues to grow

People unemployed for more than 52 weeks has climbed to almost one-quarter of the total pool of unemployed, which represents the highest level since inception of the long-term unemployment ratio in 2001 (see chart).

The financial crisis and greater job insecurity

The Westpac/Melbourne Institute survey of unemployment expectations has increased by around 50% in the past four years to a level well above historical norms, confirming that one of the key legacies of the financial crisis is a heighted level of job anxiety (see chart). Greater job insecurity might help to explain why households are saving the biggest slice of their incomes since the late 1980s and why the much anticipated re-bound in discretionary retail spending is yet to materialise.

THE RENEWED COST DISCPILINE: GOOD NEWS FOR SHAREHOLDERS, BAD NEWS FOR WORKERS

The persistent weakness in labour market conditions and renewed cost discipline are consistent with anecdotal evidence that the ASX200 companies continue to trim costs aggressively. Hills Industries has announced that it 'continues to accelerate efforts to reduce group overheads and drive further structural efficiencies in its core business' , Woolworths has committed to a pipeline of cost savings in excess of $500m in its Australian Supermarkets division, and Myer has announced a strategic review under the leadership of its new CEO and is no longer proceeding with a store opening originally planned for Greenhills in NSW.

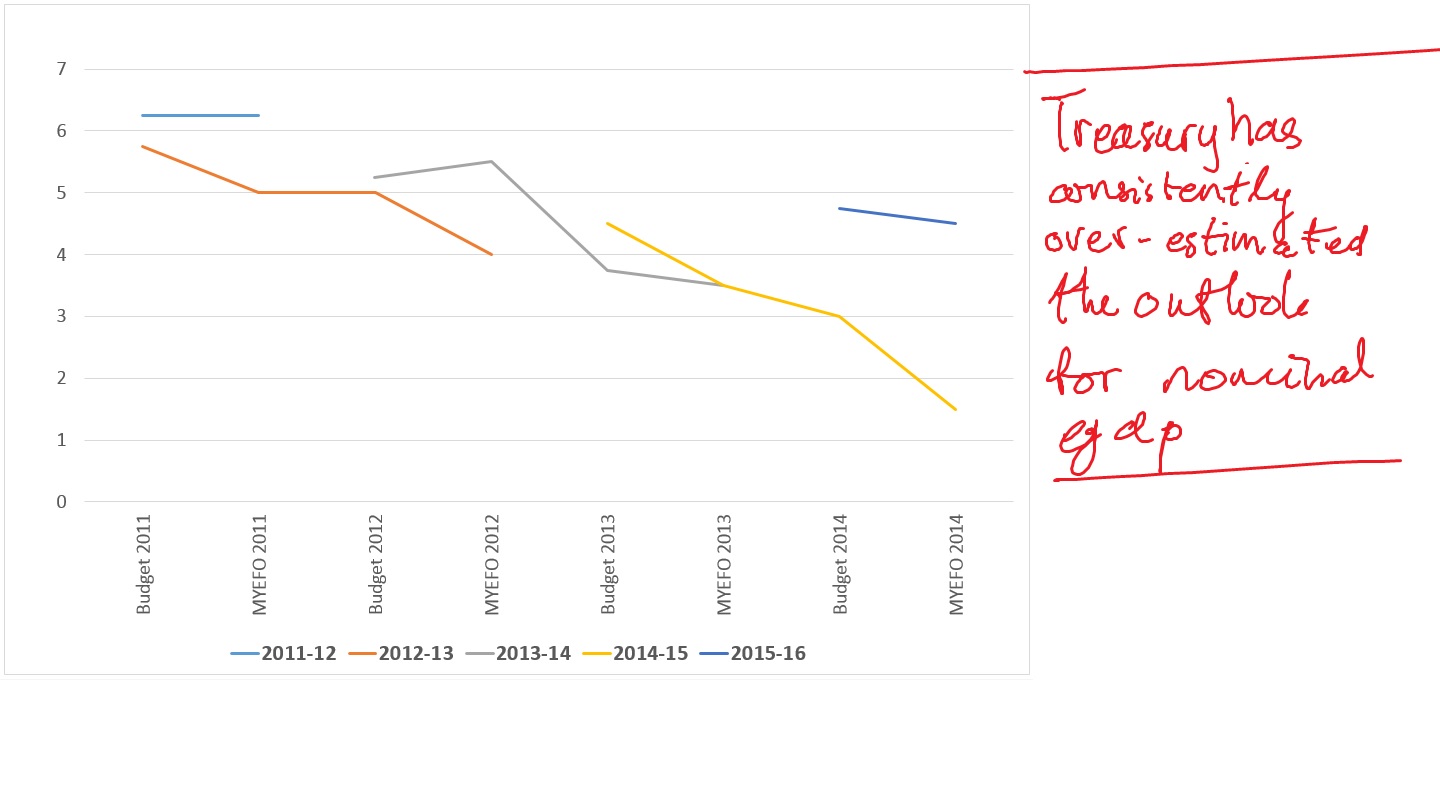

Anaemic revenue conditions continue to shape the corporate environment and the relentless focus on cost discipline. The chart below illustrates the powerful revenue headwinds that corporate Australia has faced; forecast revenues from the ASX200 companies is at the same level that prevailed four years ago, at the peak of Australia's terms of trade boom. Listed companies will therefore continue to seek ways to restructure, trim costs, and lift productivity to boost profitability and cater to investors' insatiable appetite for income. The fact that CEOs are focussing on the 'internals' or what they can control is a welcome development and a long way from chasing the pipedream of double digit revenue growth common to the credit boom years.

The renewed cost discipline is good news for shareholders but bad news for workers and job seekers. Those waiting for an improvement in labour market conditions to signal a reduction in the risk premium associated with a revival in animal spirits will need to be patient, particularly as the RBA appears to be more concerned about the growing risks from speculative activity in housing than the costs of rising unemployment and under-employment.