Tame inflation data and the bond market signal that the yield trade is yet to run its course

/As with most macroeconomic releases, there was something for everyone in today’s December quarter CPI. For the doves, the precipitous fall in petrol prices has pulled down the headline CPI which is around 1.6% higher than a year ago. For the hawks, the various measures of core or underlying inflation came in stronger than expected, growing by 0.66% in the quarter. Nonetheless, on a year on year basis, they remain close to the bottom end of the Reserve Bank’s inflation target range of 2-3%.

For the hawks, the inflation data might not offer a compelling reason for the central bank to cut interest rates. Unlike many other advanced economies, core inflation has not undershot the bank’s inflation target and the fall in the $A/$US cross rate will lead to inflationary pressures in tradeables in coming quarters. The hawks would also point to concerns that the RBA Governor has expressed about further stimulus stoking speculative activity in housing.

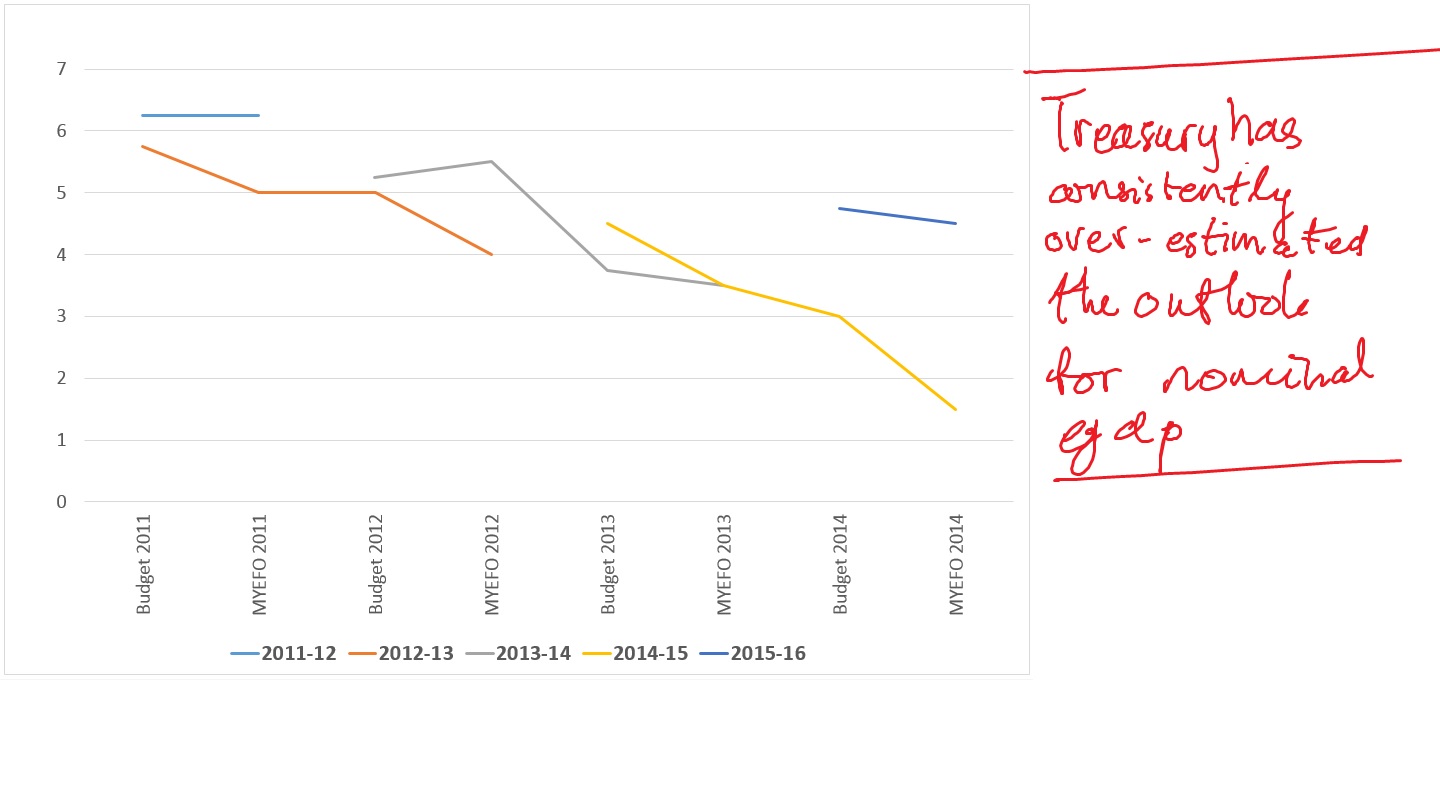

For doves, such as Evidente, the inflation data does not pose an obstacle to further policy easing for an economy that has been stuck in a nominal recession since 2011. Animal spirits remain dormant and labour market conditions continue to deteriorate. Record low growth in private sector wages and households’ heightened concerns surrounding job security – which have lifted by 50% in the past three years - point to considerable slack in the labour market (see chart).

Valuations of the yield trade are not exactly stretched

The yield trade has delivered stellar returns for quite some time now. A portfolio of high yielding stocks with strong earnings predictability or stability has produced a compound annual return of 23% in the past three years, well above the ASX200 return of 15%. Investors who have been on the right side of the trade are understandably anxious about the prospect that it unwinds against the backdrop of a cyclical re-bound.

But my quantitative analysis suggests that valuations of the yield trade are far from stretched. The basket is trading on a PE of 15 based on 12 month forecast earnings, which represents a 3% premium to the ASX200. But at times over the past three years, the basket has traded at significantly higher premiums (see chart).

Record low bond yields are not a harbinger for a cyclical re-bound

Investors concerned about the prospect of a strong cyclical re-bound would be well advised to interpret what the bond market is telling us. 10 year government bond yields have fallen recently to close to a record low of 3%. This is the lowest level since mid-2012, a period which coincided with the RBA embarking on a series of rate cuts (see chart). Clearly, bond investors are not pinning their hopes of a strong cyclical rebound anytime soon, nor are they expecting a resurgence in inflation.

The clock ticks on the global yield trade

Given the ECB’s announcement last week to expand and extend its program of large scale asset purchases, the world’s three major central banks are now aligned in their determination to address the shortfall in aggregate demand, reduce the slack in their labour markets, and boost expectations of inflation and nominal GDP. The clock is therefore ticking on the global yield trade. But it will be a while before the synchronised actions from the world’s major central banks successfully revive the dormant animal spirits in the corporate and household sectors.

Key action point: For Australia, the tame CPI print, record low bond yields and the fact that valuations of high yielding stocks with strong earnings stability are not stretched, suggest that the yield trade has yet to run its course.