Weekly Impressions - Deleveraging dynamic blunts China's Monetary easings

/Central bank communications and actions dominated financial market developments over the past week. The European Central Bank’s President re-iterated the bank’s willingness and ability to use all instruments within its mandate if warranted.

What specifically sparked the rally in global equity markets was Mr Draghi’s acknowledgement that the degree of monetary policy accommodation would need to be re-assessed at the December monetary policy meeting, thanks to downside risks to the outlook stemming from concerns over growth prospects in Emerging Markets and related developments in financial and commodity markets. Although Mr Draghi cited these concerns at the September press conference, at that time, he suggested that it was too early to assess whether these developments would be transitory.

The shift in Mr Draghi’s rhetoric at last week’s press conference confirms that that the ECB assesses that the risk has increased that these developments – if left unaddressed - could have a long lasting impact on the outlook for prices.

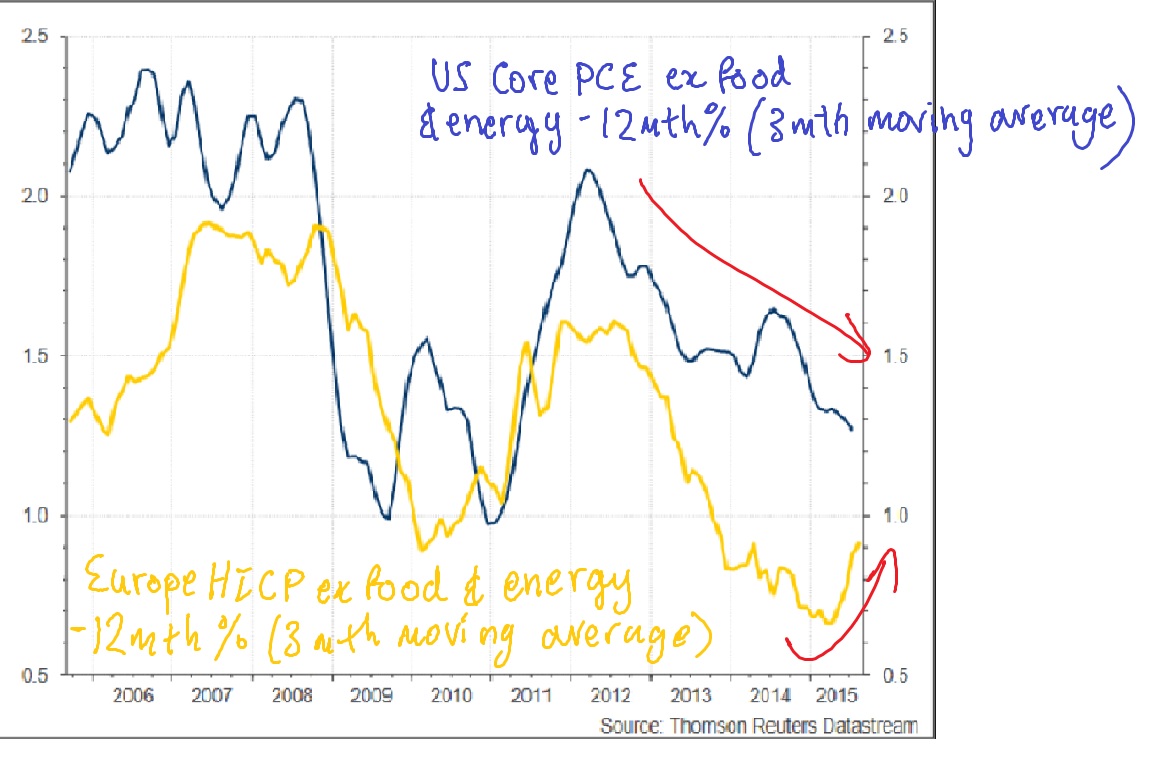

Core inflation has undershot the ECB’s target for the past decade

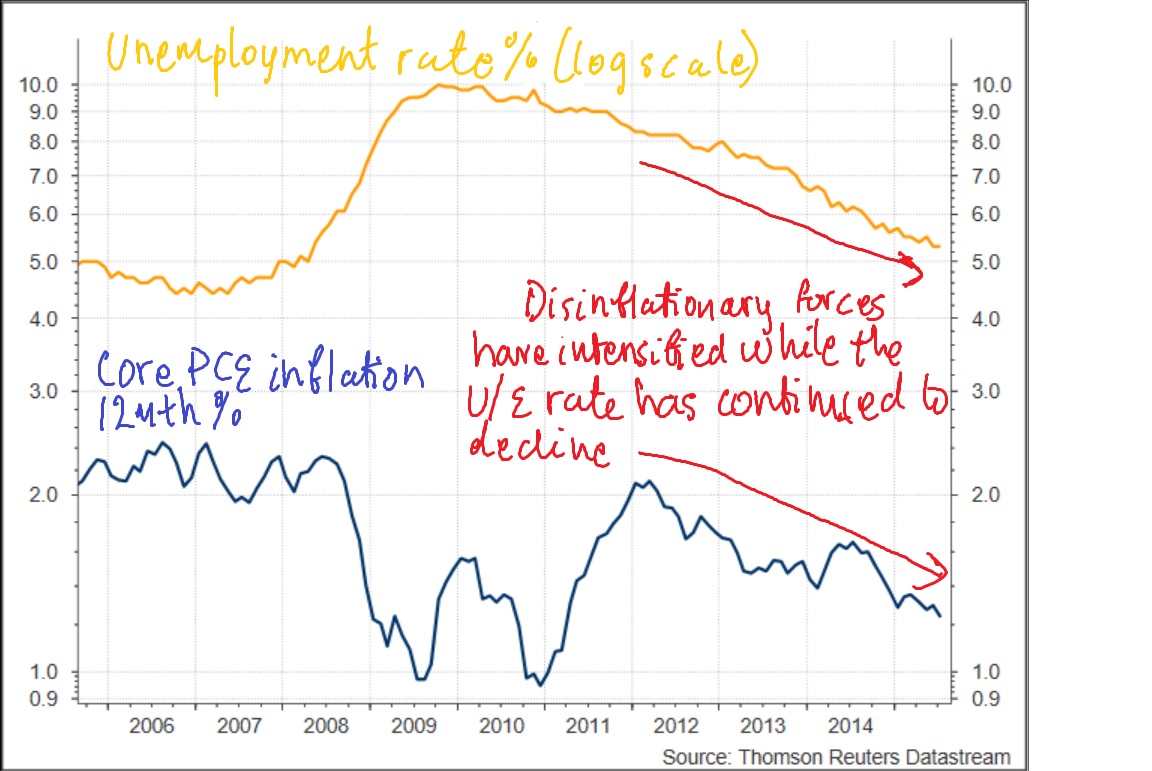

On that measure, the ECB’s more aggressive rhetoric and stimulus this year reflects a belated acknowledgment that it should receive a fail for its continued inability to meet its inflation target, which is to achieve an inflation rate below but close to 2% over the medium term. Over the past decade, the core Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices has consistently failed to get anywhere near 2%, with the exception of 2007 and 2008 (see chart). Although inflation has picked up this year, the year-on-year rate still doesn’t have a 1 in front of it.

The strength and persistence of global disinflationary forces since the financial crisis suggests that the ECB will need to extend (and probably expand) the asset purchase programme to beyond September 2016. Expect global equity markets to rally on this announcement.

As an aside, the ECB’s inflation target is too high. Once the upside bias in the measurement of consumer price indices is taken into account – particularly the rapid innovation in the provision of IT and related services – a 2% inflation target translates into modest deflation. Evidente will explore this in more detail in a forthcoming research report.

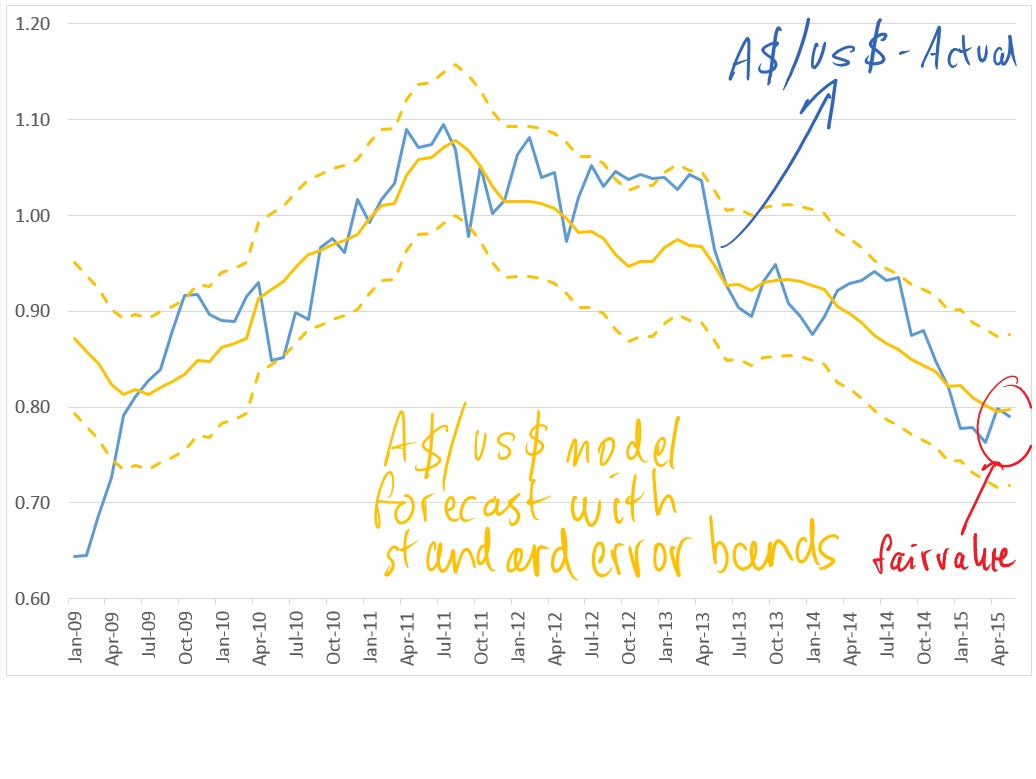

Someone forgot to tell global stock markets about ‘currency wars’

The euro depreciated against the US dollar by 3% on the announcement to its lowest level in two months (see chart). The zero sum game embedded in ‘currency wars’ predicts that outside of Europe, stock markets should have fallen on the ECB’s announcement due to adverse effect of euro depreciation on the competitiveness of non-European exporters. But not only did European stock markets rally strongly but so did global stocks, including stock markets in the United States. The overwhelming weight of evidence supports the view that monetary stimulus works by boosting consumption and investment, not net exports.

Deleveraging dynamic blunts China's policy easings

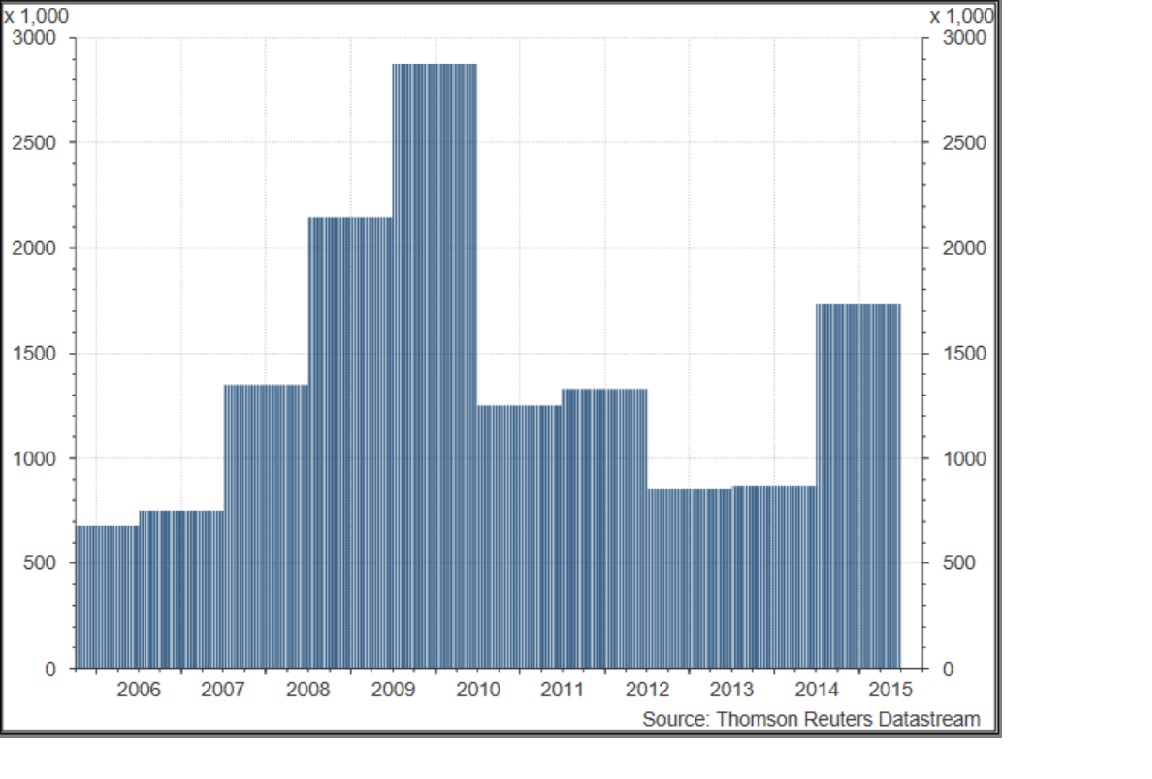

China’s central bank cut its 1 year benchmark bank lending rate by another 25 basis points to 4.35%. This represents the sixth cut in twelve months, bringing the cumulative decline to 165 bps since November 2014 (see chart). The benchmark deposit rate was also cut by 25 bps to 1.5% and the reserve requirement ratio (the amount of reserves held be banks) was reduced by 50 bps for all banks.

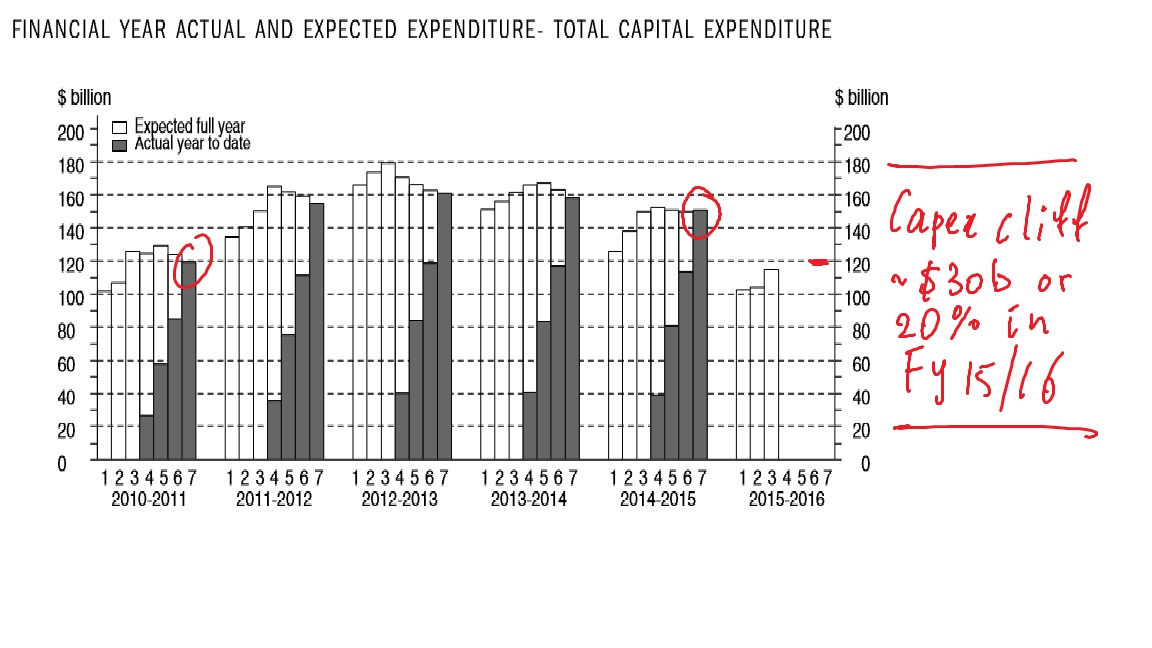

The additional policy stimulus is designed to moderate the continued slowdown in various activity indicators, including fixed asset investment and industrial production (see chart).

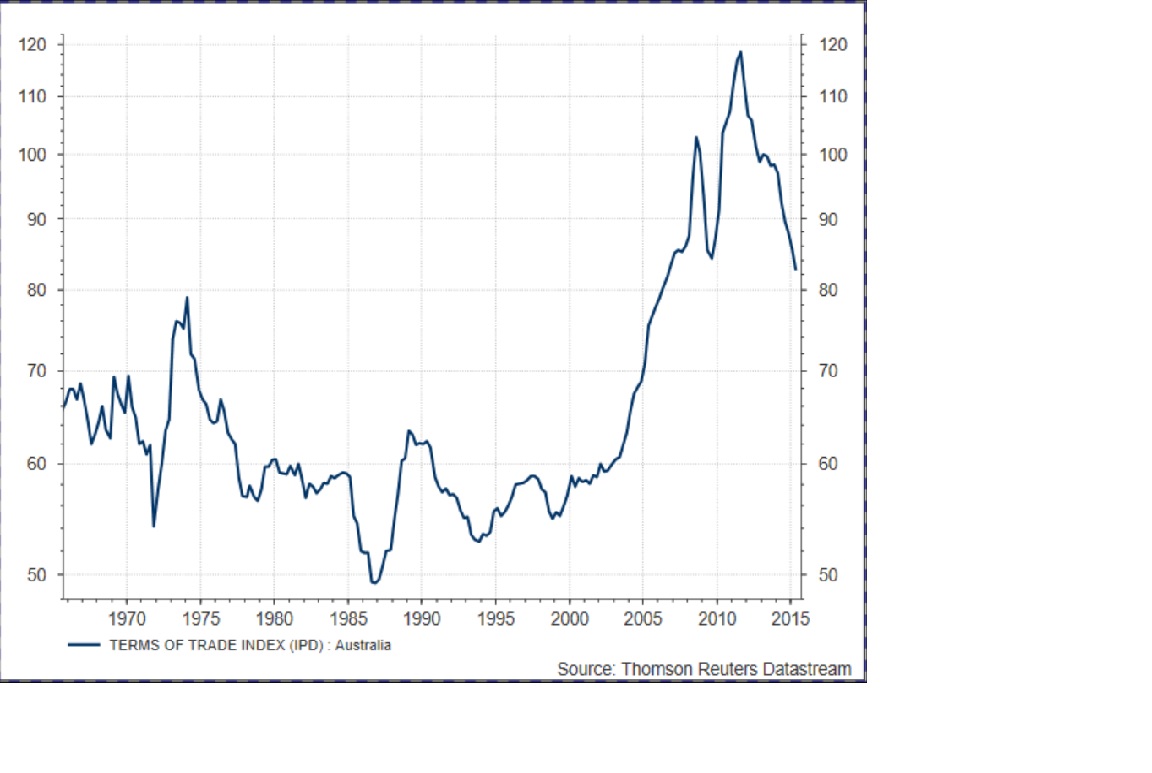

Growth in industrial production has been particularly weak for construction related products. Steel industry conditions remain weak, with domestic production having moderated. Against this backdrop, domestic iron ore production and iron ore imports (including those from Australia) have trended lower (see chart).

The policy easing thus far has done little to mitigate the ongoing deleveraging dynamic in China. Growth of total social financing continues to moderate due primarily to a sharp slowdown in off-balance sheet financing activity, reflecting both cyclical and regulatory developments (see chart).

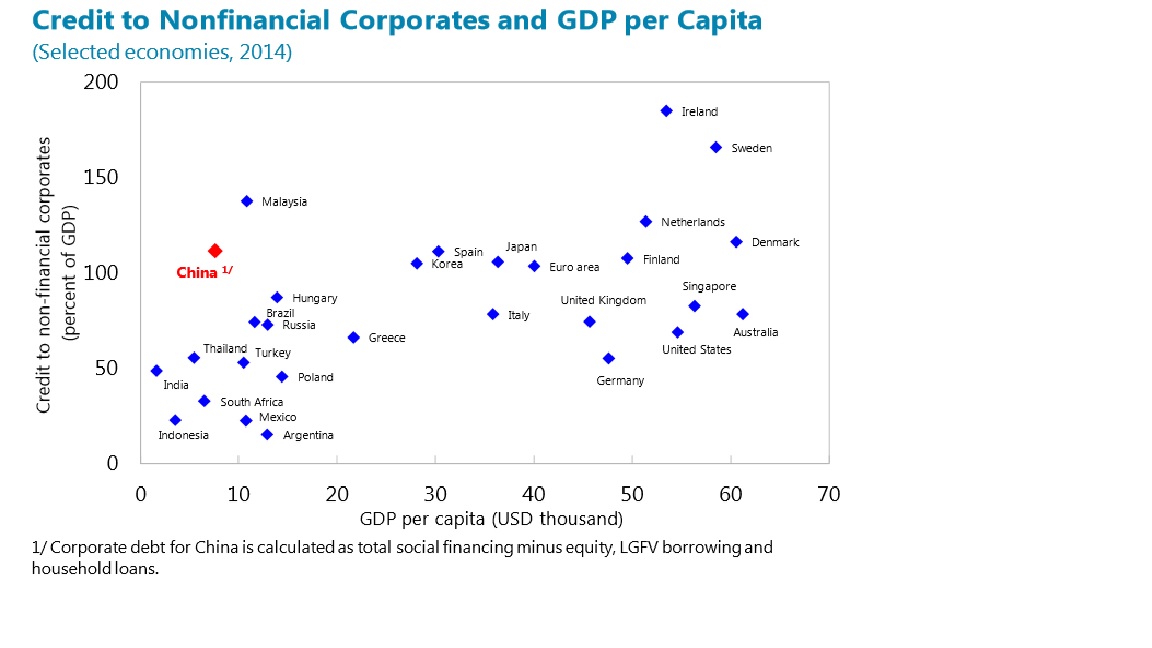

A number of other key developments are weighing on activity and working to blunt the efficacy of monetary policy in China: low efficiency of investment, the decline in corporate profitability, lower interest coverage ratios for SOEs and other excess capacity sectors even as interest rates decline, and the high debt burden of the non-financial corporate sector (see chart).