Australia's housing revolution continues...but for how much longer?

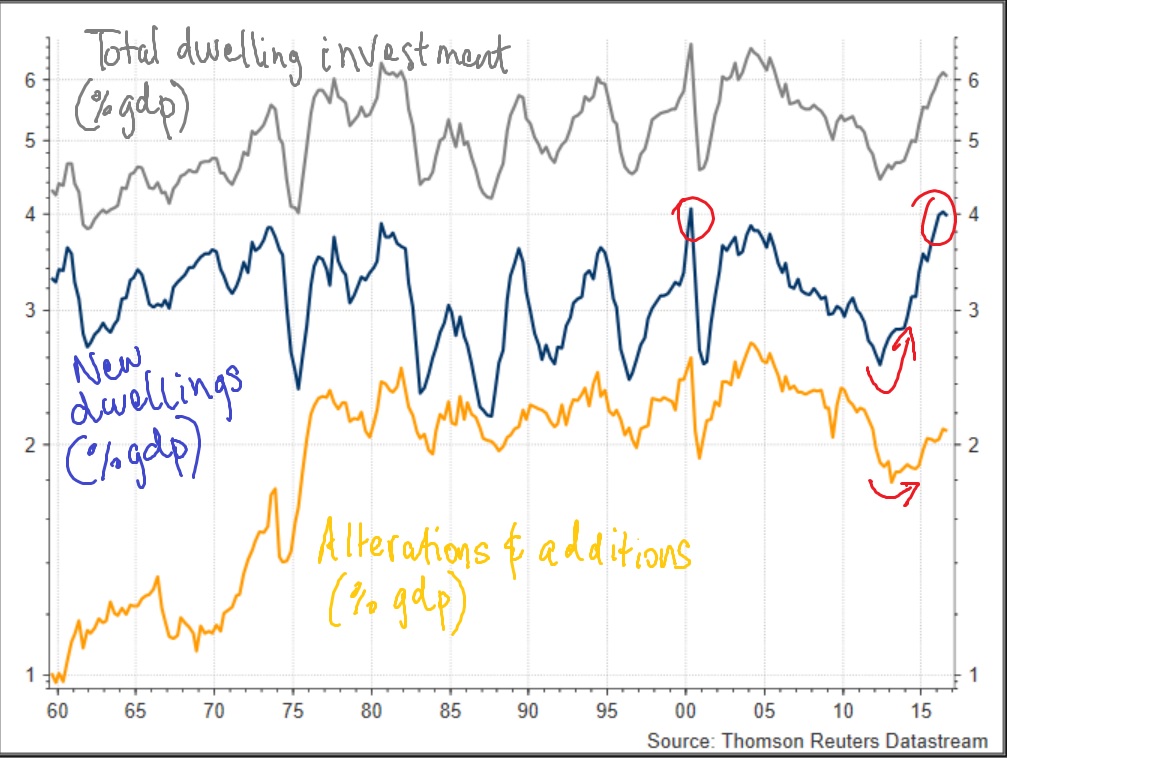

/Dwelling investment represents one one of the highly cyclical components of aggregate demand. Since the inception of the National Accounts in the late 1950s, investment in housing has been subject to numerous cycles, but in the past dozen years the cycle has become more extended and less volatile (see chart). At present, total dwelling construction accounts for 6% of GDP, a peak reached only five times in the past sixty years. Usually, housing activity of this scale has reflected overbuilding, and subsequently been followed by a sharp downturn, including: the 1980s, mid-1990s, early 2000s and mid-2000s.

New dwelling investment close to a record high

What is particularly unique about the housing expansion since 2012 is the composition of dwelling investment. The GDP share of renovation activity - 'alterations and additions' - remains low by historical standards at around 2%. This was the basis for Evidente suggesting in prior posts that the renewed growth in house prices this time didn't reflect an emerging property market culture, like that which prevailed in the early 2000s, when renovation activity lifted to 2.6% of GDP. Many home-owners became DIY experts over this period, and the turnover of the housing stock lifted as owner-occupiers sought to renovate and sell quickly at a handsome profit. Rather, new dwelling investment has underpinned the current expansion, which has lifted to 4% of GDP, its highest level since 2000/01 (see chart).

Australia's apartment boom

The second dimension of Australia's housing revolution has been a shift towards higher density living; Australia's apartment and townhouse boom. The number of residential building approvals for higher density dwellings is now comparable to that for detached houses, at between 110k and 120k per annum (see chart).

In its February Statement of Monetary Policy, the RBA notes that within the higher density segment, there has been a shift towards apartment blocks with four or more storeys (see chart).

Australia's housing revolution towards higher density living has been felt across the entire eastern border; the number of residential building approvals for apartment blocks and townhouses has posted strong growth since 2012/13 across NSW, Victoria and Queensland (see chart). In the past year however, there has been a substantial drop in high density approvals in Queensland and Victoria, probably reflecting the tightening of bank lending standards to housing investors and lower price growth. The RBA notes that the boom in apartment construction has been particularly concentrated in inner city Brisbane and Melbourne, which make these cities vulnerable to rising risks of over-supply emerging.

According to the RBA, the number of cumulative apartment building approvals in the three years to 2015 added around one third to the stock of apartments in both inner city Brisbane and Melbourne, but less than one-fifth in inner city Sydney. These divergent trends probably reflect the relative scarcity of available land for development in inner city Sydney.

Why the shift to higher density housing?

Higher population growth

A lift in population growth in the past decade has supported the dwelling investment cycle. Year on year growth in the population has remained above 1.4% for much of the past decade (see chart). This follows a fifteen year period in which population growth typically was below 1.2% pa.

Evolving consumer preferences towards more affordable living

Higher population growth can explain some of the shift towards higher density living thanks to land supply constraints, which have been associated with higher prices for blocks of land and detached houses. This has induced a shift in consumer tastes towards apartments, which use land more intensively and are therefore more affordable than detached houses.

Limits to the urban sprawl

Given the topography of Australia's major cities, there are physical limits to further urban sprawl. Consequently, there has been an increase in the availability of former industrial or brownfield sites relative to urban fringe or greenfield sites, which are mostly used for detached housing.

Australia's low urban population density slowly catching up to the rest of the world

Despite the shift towards higher density housing, Australia's urban population density remains amongst the lowest in the world, which reflects postwar policies designed to encourage construction of detached housing on suburban land blocks - particularly for war veterans and their families - and the culture of aspiration for a house on a quarter acre block (see chart).

Australia's housing revolution - Here to stay

Evidente believes that developments that have led to the shift towards higher density living are likely to persist over the medium term: limits to further urban sprawl, shift in preferences to the convenience of living close to employment centres, Australia's still low population density and the waning aspiration of owning a detached house on a quarter acre block.

- Given the topography of cities such as Melbourne and Sydney, there are limits to which the urban fringe can further expand, not to mention the high transport infrastructure costs associated with developing greenfield sites that are more distant from the city. The aversion of Australia's governments to lift debt levels or raise tax rates to fund infrastructure has seen a rush of sorts to sell or lease government assets. For instance, the Victorian government last year announced the long-term lease of the Port of Melbourne, with the proceeds linked to the replacement of around 50 railroad crossings across metropolitan Melbourne.

- The growing demands of white collar occupations are such that many workers in these roles will want to continue to live close to employment centres, in addition to the convenience and diversity of choice associated with living in or close to the inner city.

- Australia's population density remains low by international standards. The scope for Australia's capital cities to accommodate a growing population and increase population density probably depends in part on an easing of planning laws that allows higher apartment towers to be built across metropolitan areas.

- The substitution effect from detached housing to townhouse and apartment living is expected to continue. Notwithstanding the risk of a correction in house prices, the average price of residential land and detached houses is likely to remain high, encouraging people - particularly young people - to live in more affordable, higher density housing than their parents were accustomed to. Against the backdrop of the shift that has already been occurring, the aspiration to own a detached house with a good size backyard on a quarter acre block is not ingrained in Australian culture as it once was.

Investment implications - The long view...

Planning laws have promoted the development of apartment buildings and other high density dwellings along major roads and railway lines, that have easy access to public transport. But the demand on existing infrastructure is such that congestion has continued to increase. Traffic congestion remains a political hot potato for Australia's federal government, as well as state governments, particularly in the two most populous states, NSW and Victoria. In addition to the removal of 50 railway crossings across metropolitan Melbourne cited, a number of other transport infrastructure projects are underway, including the construction of Melbourne's metro tunnel and the widening of Transurban's City Link.

Evidente believes that the two listed stocks most leveraged to the construction of infrastructure projects designed to ease traffic congestion are toll road operator, Transurban, and Downer, which generates over one-third of its revenues from its rail and transport services divisions. Downer has lifted its operating profitability in recent years to over 20%, continues to trade at a discount to the broader market, and has a sound balance sheet with a gearing ratio (which includes off balance sheet debt) of less than 15%.

Hardware retailers such as Bunnings might need to modify their product range over the medium term, with the growing army of apartment dwellers presumably having less need for garden appliances and power tools. Moreover, there is less scope for apartment dwellers to engage in DIY renovation than those living in detached houses.

...but don't forget the cycle

Despite the prospect that the structural shift towards higher density housing will continue over the medium term, booms and busts around the new normal are inevitable. As cited above, new dwelling construction remains close to a record peak of 4% of GDP. The RBA has already warned about the growing risks of an apartment oversupply emerging in inner city Melbourne and Brisbane. By late 2016, half yearly growth in inner city apartment prices in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane had trended down to zero (see chart).

If conditions in these markets deteriorate substantially, banks would likely experience more material losses on their development lending than on their mortgages. Development lending is typically associated with a higher default probability and higher loss given default than on their mortgage lending for apartment purchases. Nonetheless, banks' aggregate exposures to inner city apartment markets- particularly in Sydney - are greater through their mortgage lending than via development lending (see chart). The aggregate dollar value mortgage exposure translates to 2-5% of banks' total outstanding mortgage lending to inner city Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane.

Australian mortgage lending has historically been profitable due to low default rates - around 1/2 per cent - and high levels of collateralisation. Price growth of inner city apartments in Sydney has been strong in recent years, so that a large price fall would be necessary for banks to experience big losses due to lower loss given default assumptions. The buffers are smaller for Melbourne and Brisbane because capital appreciation in apartments has been subdued. The RBA estimates that combined inner city apartment values across Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane would need to fall by 25% or more before banks started to incur significant losses.

In its quarterly update this week, the CBA showed its exposure to apartment developments by city, which amounts to a little over $5 billion in aggregate. Sydney apartments represent 60% of its exposure where the buffer is larger, while Melbourne and Brisbane in total account for a little under 30% (see chart). The total loan to value ratio of 60% is conservative and the CBA indicates that it has lowered its share of foreign pre-sales.

Despite these risks, Evidente's model portfolio remains modestly overweight Australia's bank sector. Although the P/B discount that banks trade on relative to industrials has narrowed in recent months, it remains high by historical standards (see left panel below). The sector's ROE has dropped in part thanks to de-gearing associated with a lift in loss absorbing capital buffers, but the ROE prospects for the industrials universe have deteriorated by more (see right panel).