Weekly Impressions - Australia's policital culture at a cross-roads

/The decision by the Coalition government to replace its leader, Tony Abbott, with Malcolm Turnbull dominated developments in Australia in the past week. Much of the commentary has drawn parallels with similar machinations in the previous government, in which Julia Gillard replaced Kevin Rudd in his first term as Prime Minister. Much has also been made of the renewed instability of Australian politics, which has seen five Prime Ministers in as many years.

Many political commentators have discussed the different style in communication that Mr Turnbull will bring to his Prime Ministership. Indeed, Mr Turnbull himself has flagged that the Government will need to do a better job in articulating an economic vision for Australia. Whatever that vision is – which he is yet to articulate – Evidente’s view is that four key factors will constrain the new Prime Minister’s ability to execute on that vision: the stark reality of the Senate, Australia’s terms of trade shock associated with China’s slowdown, the country’s wage recession, and the wedge between government revenue and spending.

The Senate’s stark reality

Australia’s Senate or Upper House of Parliament is composed of 76 seats; 12 from each of the six states and two from the two territories. Most Bills are initiated in the House of Representatives or the Lower House, but need to be passed in the Senate.

The Coalition Government (composed of the Liberal and National parties) falls well short of the 39 seat majority required. At present, the Coalition holds 33 seats, followed by the Australian Labor Party (ALP) with 25 seats and the Greens with 10 seats. The remaining 11 seats are held by various independents and small minority parties (see exhibit).

In recent decades, it has been common for the Government of the day – which holds the majority in the House of Representatives – to rely on other parties to achieve a majority in the Senate. But the Senate has become more hostile in recent times, with the emergence of the Greens as the third force in Australian politics, effectively displacing the Australian Democrats, which had been a centrist party. The Greens’ left wing origins mean that it more commonly votes with the ALP, so that the Coalition must rely on the support of a disparate group of mainly populist independent and fringe parties.

The Abbott Government discovered the Senate's hostility when it failed to garner support in the Upper House for two key items in its first Budget in 2014: the Medicare co-payment of $7 for a visit to the doctor and the deregulation of higher education, both important reforms designed in part to address the growing budget deficit. The great expectations that Canberra’s press gallery and the community have for the Turnbull Government are unlikely to be met thanks to the stark reality of the Senate.

Australia’s wage recession

Australia’s wage cost index is only 2.3% higher than a year ago, which represents its slowest annual growth since the inception of the series in the late 1990s and well below growth at the peak of the financial crisis (see chart). The wage recession suggests that the demand for labour remains weak. Renewed strength of employment growth in recent months might be an early sign that low wages growth is encouraging businesses to lift their hiring intentions.

Sluggish wages growth might help to explain the adverse community reaction to the travel rorts affair recently, which claimed the scalp of the Speaker of the House of Representatives, Ms Bronwyn Bishop. From the perspective of the new Turnbull Government, the community’s appetite for economic reform will remain limited thanks to Australia’s wage recession.

Let’s not talk about the elephant in the room

The former Treasury Secretary, Mr Martin Parkinson, has been vocal for some time about the conversation that politicians have not had the courage to have with the community around the divergence between government revenues and expenditures. After growing in line with government outlays during the credit boom, tax revenue dropped sharply during the financial crisis and although it has recovered since then, it hasn't kept up with the path of government spending (see chart).

At the coal-face, social reforms such as the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) have received bipartisan support, but there has been little public debate about how the costly scheme will be funded.

The Turnbull government faces a delicate task between not further undermining already fragile consumer and business confidence in the short-term, but putting its financial position on a sustainable footing over the medium term by addressing the growing wedge between government revenues and expenditures. At a time when wages are growing at a record low, perhaps the community is not ready to have this conversation just yet.

The terms of trade shock

Like the Abbott and Gillard Governments, the economic fortunes of the Turnbull Government will be hostage to China’s future growth prospects and Australia’s terms of trade – the price it receives for its exports relative to the price it pays for its imports. Growth in China’s industrial production and fixed asset investment has continued to moderate in the past year, while annual retail sales growth has remained at 10% for the past four years (see chart).

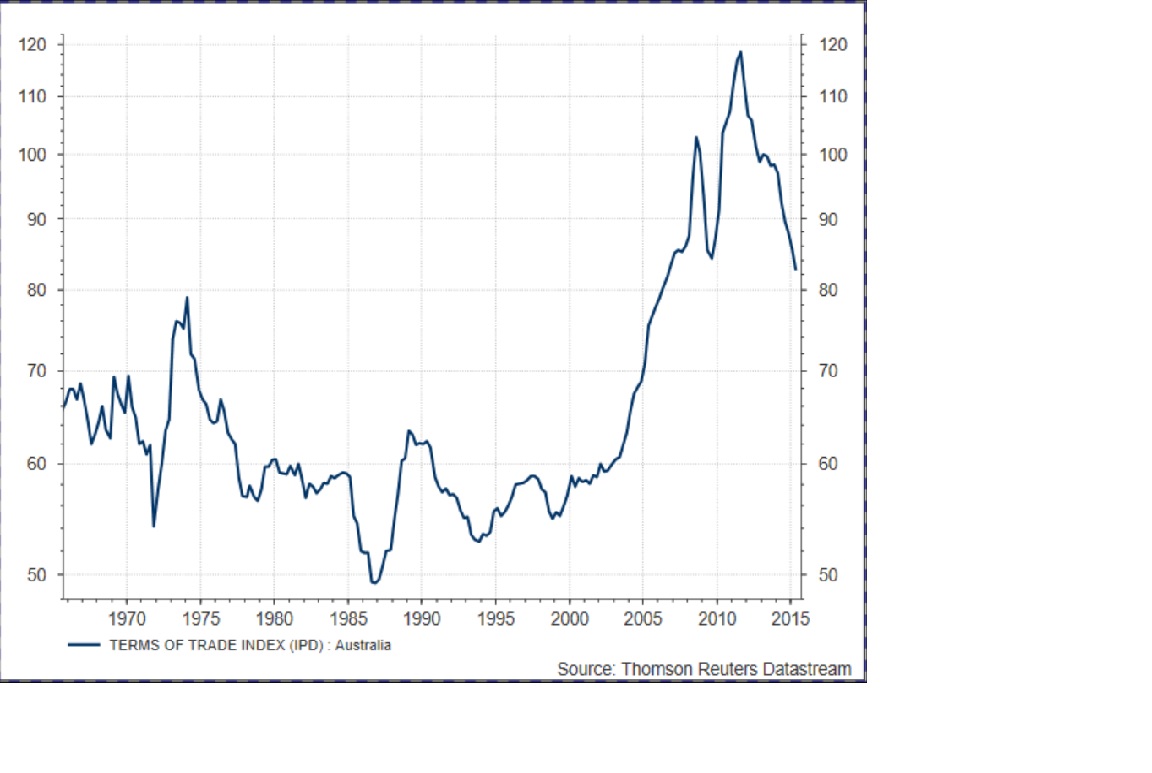

Against this backdrop, Australia’s terms of trade has declined by 30% from its peak in 2011, which has been an important drag on growth in nominal GDP. Despite this, the terms of trade remains well above historical norms (see chart).

Importantly, there are renewed concerns about the authorities' ability and willingness to stimulate the economy, re-balance growth from investment to consumption, and undertake necessary reforms to State Owned Enterprises. Further weakness in markets for Australia’s key export commodities – iron ore and coal – will undermine the Turnbull Government’s capacity to undertake budget repair.